Who was Heinrich Hoffmann?

1809

Heinrich Hoffmann was born on June 13th, 1809 in Frankfurt am Main. His mother died before his first birthday. His father was simultaneously a master-builder

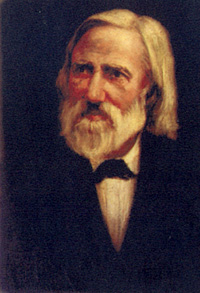

Heinrich Hoffmann

and a city building inspector. In 1813, Heinrich’s father married the sister of his dead wife, in whom Heinrich found a loving stepmother. The family lived modestly in several of Heinrich’s father’s newly constructed houses. Besides his time in school, Heinrich Hoffmann spent his whole life in Frankfurt am Main, which until 1866 was wholly independent.

1829-1833

Heinrich Hoffmann could not make ends meet pursuing his passion for writing. He began to study medicine at the request of his father. He studied in Heidelberg, Halle, and Paris until 1833. His fellow students nicknamed him Rabbit because he often abstained from drunken rowdiness in favor of spending time in nature and hiking.

1835

Hoffmann established himself as a general practitioner in the Sachsenhausen district of Frankfurt am Main. Here he lived modestly in the Gasthof zum Tannenbaum. Along with his colleagues, Hoffmann looked after a clinic for the poor, in which patients from nearby towns and with little money were treated free of charge. For Hoffmann, this extension of his student life was a happy time. He wrote many poems, which he published as a book in 1842, though to little financial success. He shined, however, as a speechmaker at official events, including the 1844 dedication of the Goethe monument.

1840

In this year the young doctor with an insecure income married Therese Donner, the daughter of a distinguished merchant. The first of their three children, Carl Philipp, was born a year later in 1841. It was with a gift to this child that Heinrich Hoffmann would become world famous.

1844

Hoffmann received in this year the highly sought-after position of anatomist at the Senckenbergisches Institut. The year would become historically significant, however, by way of a trifle. At Christmastime, Hoffmann was searching for a children’s book to give to his three-year-old son. Disappointed by all he found, Hoffmann decided that he himself would compose the book. He purchased a blank notebook and got to work. By Christmas Eve the book lay beneath the tree.

1845

Were it not for the publisher Zacharias Löwenthal, it is certain that nothing more would have come of this little book. He read it by chance, and recognized in it an original kind of children’s book, and pressed Hoffmann to publish it. Hoffmann, however, was hesitant. Perhaps he was afraid of what the publication of a book for children could do to his reputation as a respected doctor and poet. Nevertheless, “on a bright, wine-influenced whim,” he consented. In the first edition, however, Hoffmann appears under the pseudonym “Reimerich Kinderlieb.” In 1845, the first 3,000 copies of the book came onto the market (not 1,500, as Hoffmann once indicated), and were quickly bought up. From then on there have been countless editions of the work.

Hoffmann published five other books for children, including King Nut-Cracker or The Dream of Poor Reinhold (1851). None of these, however, were able to repeat the success of the Struwwelpeter. Hoffmann also wrote humorous books for adults, two political satires during the 1848 revolution, among other things. In 1873 he published his final work, a collection of poetry, called “On Bright Paths” (Auf heiteren Pfaden).

1848

Heinrich Hoffmann was also politically engaged. In March of 1848 he celebrated the revolution against princely rule with his lyric “Listen Well, my People” (“Horch auf, mein Volk”). Hoffmann was a moderate liberal, who argued for a constitutional monarchy under Prussian rule. He was a member of the pre-parliament, which organized the first German national convention in Frankfurt’s Paulskirche.

1851

Hoffmann’s lifework was accomplished in his position as a doctor. In 1851 he became the executive of the “Institute for the Epileptic and Insane” in Frankfurt. Hoffmann, who had never before experienced working in such a ward, found his calling there. From then on he pursued the goal of the betterment of his patients’ living circumstances.

Hoffmann, in this time, pursued his work with a medical perspective that was unique at the time, that is, to treat his patients as victims of illnesses that could be treated and helped with the proper medicines. Before this time the mentally ill had been viewed as lazy, unwilling to work, or possessed by the devil. They were treated as criminals and often locked away in prisons. Hoffmann worked for years to change these common misperceptions. Hoffmann’s psychiatric case studies of mental disorders and epilepsy (1859) were published as part of his effort to gain clearance to have a new building constructed for his institute. With his imagination and perseverance, Hoffmann’s plan was eventually realized, and construction began on this exemplary psychiatric clinic, despite protests from other parties. The clinic was dedicated before the gates of the city at Affenstein in 1864. It was nicknamed the “Mad Castle” (“Irrenschloß”) by residents for its magnificent, neo-gothic design. Hoffmann lived there with his family until his retirement in 1888.

1894

Heinrich Hoffmann died in his hometown of Frankfurt am Main on the 20th of September.